In computer graphics one of the biggest difficulties is handling scenes which are both way too large to fit into memory and way too detailed to be processed all at once by the graphics hardware.

This article touches on the second part. Recently I had to experiment with ways to quickly throw out a lot of work items which do not contribute to the main scene, and for the ones that do, determine at what level of detail (LOD) they should be rendered at.

The result is a combination of view frustum culling, multiple LODs per mesh, and splitting each mesh into batches of smaller meshes called “meshlets”.

This has been implemented into StratusGFX for version 0.10 (still in development). Source code is available in one of its dev branches.

Pros

- Very easy to understand and implement with help from 3rd party libraries

- Extensible: meshlet bounding boxes can be checked via brute force means or extended to the more efficient bounding volume hierarchy (BVH) approach

- Plays nicely with GPU-driven work generation

Cons

- Takes some tweaking to figure out a good upper bound on how many meshlets a mesh should be split into

- Does not take into account the area a meshlet bounding box takes up on screen which may lead to less than ideal LOD selection

Data Storage

Each mesh and all of its LODs are stored in a giant GPU buffer and accessed from shaders using SSBOs. More information on this can be here and also here.

With this setup there are actually two buffers. The first stores all of the mesh data (vertices, normals, etc.) and the second stores all the indices for use with indexed rendering. Each LOD for each mesh is laid out one after the other. So the base mesh sits in the first slot followed by all its LODs, and after the final LOD an entirely separate mesh starts.

Splitting and Optimizing the Mesh

This step can be carried out in any way that makes sense for the application. For this implementation two 3rd party libraries were used: Assimp and MeshOptimizer.

During the first stage, Assimp loads the mesh. The main flags that are of interest include configuration item AI_CONFIG_PP_SLM_TRIANGLE_LIMIT along with the process enum aiProcess_SplitLargeMeshes. Together these allow you to tell the library that large meshes should be split into smaller meshes based on the triangulation upper bound that you set.

Once this is done, each submesh is passed into MeshOptimizer using its meshopt_simplify function. This will generate a new simplified mesh based on the data of the input. To generate simpler and simpler LODs, pass in the result of the previous call to simplify to get an even simpler output.

For StratusGFX, the simplification stops after either 7 LODs have been generated for a total of 8 datasets if the base mesh is included, or if any of the generated LODs fall below 1024 total triangles.

Bounding Boxes

For this the engine generates an Axis-Aligned Bounding Box (AABB) for each submesh/meshlet. This same AABB is reused for of that meshlet’s LODs. For more information about creating and using AABBs, see here.

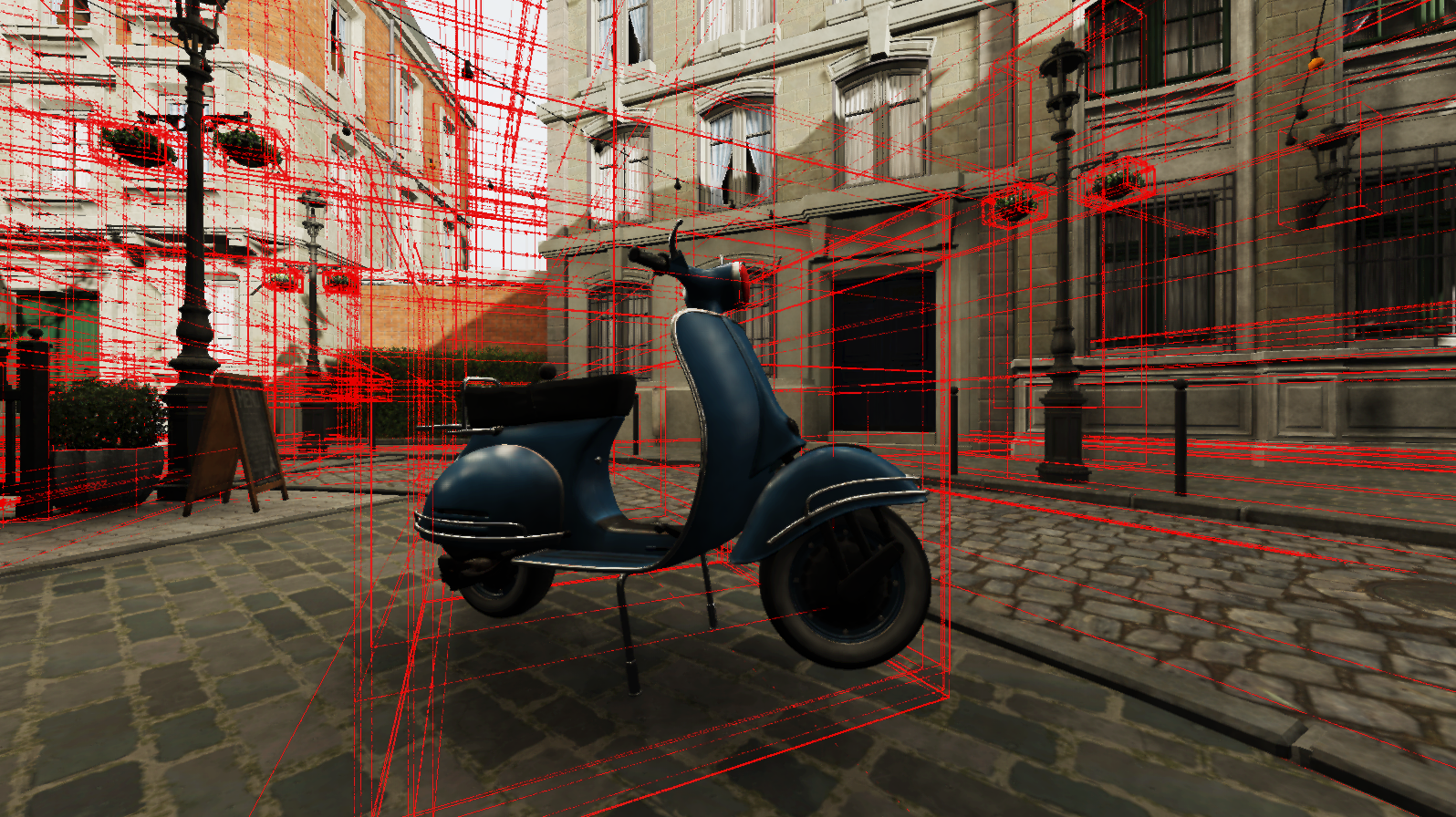

The end result looks like this:

If you look closely you will see multiple bounding boxes within the different objects in the scene. After an object is loaded and split into submeshes/meshlets, each submesh gets its own bounding box which can be used to determine if that particular submesh is within the view frustum. Setting a higher maximum number of triangles per submesh results in less submeshes but potentially less performance while the same is true for the reverse situation, so it takes some trial and error to find a good value.

Determining Visibility And LOD

Each submesh draw commands are stored in a global draw command pool per type (for example, static objects go in their own pool separate from dynamic objects - this helps to better reuse work between frames). These commands are stored inside of GPU memory which enables compute shaders to be utilized to enable/disable certain commands.

What this means is that for this step, the GPU both determines visibility (enable/disable the command) as well as the LOD (sets the index into the global mesh data pool for use during drawing for that draw command) which greatly speeds up this process. With this setup the CPU sets up the initial data and then dispatches a compute work group to do the rest. For more information, see this post about Multi-Draw Indirect which goes over how this works with OpenGL.

For visibility, the GPU uses simple AABB bounds checking against the view frustum described here.

Finally, for LOD selection the GPU determines how far away the submesh’s bounding box is from the camera. To do this it computes the nearest point of intersection between a ray originating at the camera and moving in the direction of bounding box. The length of the line between the point of intersection and the camera is the distance which is then used to select the LOD. This requires some trial and error as well to figure out good cutoffs (for example, at what distance does it move from LOD 2 to 3? etc.).

Here is the GLSL shader code which determines the distance from point to bounding box:

float distanceFromPointToAABB(in AABB aabb, vec3 point) {

float dx = max(aabb.vmin.x - point.x, max(0.0, point.x - aabb.vmax.x));

float dy = max(aabb.vmin.y - point.y, max(0.0, point.y - aabb.vmax.y));

float dz = max(aabb.vmin.z - point.z, max(0.0, point.z - aabb.vmax.z));

return sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy + dz + dz);

}The downside of this method is that while it is simple and easy to setup, it does not factor in how much space on the screen the bounding box takes up.

Conclusion

Once this was implemented a lot of performance was gained especially in the more complex scenes. Being able to eliminate a lot of GPU work based on what the camera is actually looking at and how far away it is has a huge impact on how well the scene can run.

In the future more advanced methods will likely be explored such as organizing the scene into one or more BVHs and also taking into account how much screen space a particular AABB occupies.