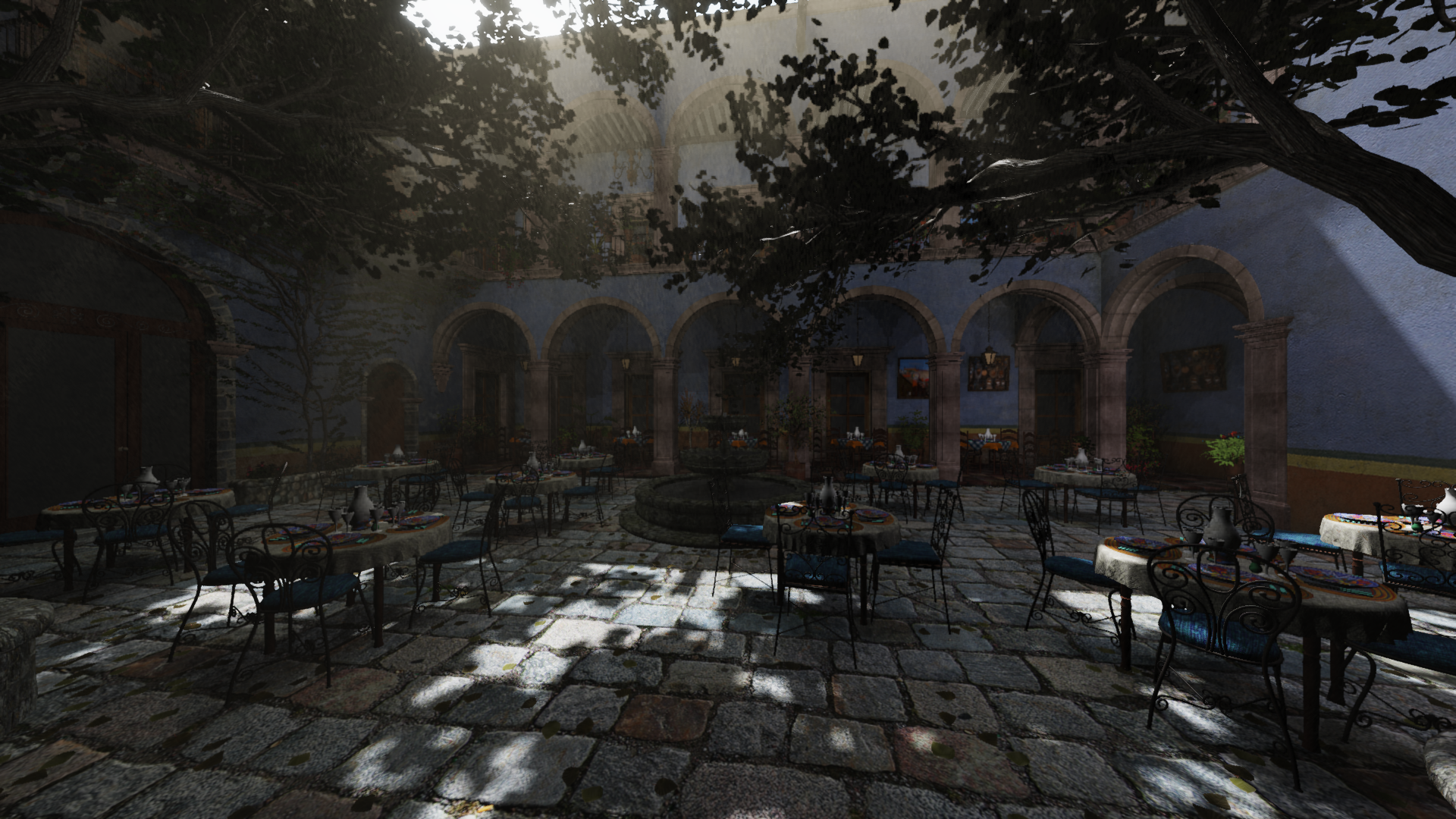

(rendered with StratusGFX - model is Intel Sponza 2022)

(rendered with StratusGFX - model is Intel Sponza 2022)

This article will breakdown a lot of the high level technical details of how StratusGFX renders a single frame. A feature reel can be found here.

StratusGFX is a realtime rendering engine I wrote in order to learn about modern graphics programming techniques. Development and testing was done on Windows 10 running with a Ryzen 5 1600 and an Nvidia GTX 1060. The target frame rate was a minimum of 30 fps (33.33 msec), but most of the scenes in the tech demo ran at 60 fps (16.67 msec) a majority of the time.

This frame was rendered with engine version 0.9.

How A Frame Is Rendered

StratusGFX makes heavy use of programmable vertex pulling with bindless resources. This allows for all scene mesh data to be allocated from a single giant GPU buffer which all subsequent rendering queues reference.

Bindless resources mean that the renderer can determine at the start of the frame which textures need to be used (shadow maps, diffuse maps, normal maps, etc.) and ensure that they are all made resident on the GPU before any draw calls are made.

These two approaches enable a very important optimization technique known as draw call merging. For example, the renderer can batch up all static opaque meshes into one render queue and then dispatch them with one call to glMultiDrawElementsIndirect. This also makes it possible to cache previously generated render queues and reuse them in future frames if nothing has changed.

Another interesting opportunity is also created by using this approach. Since all materials and their textures are made resident at the start of the frame, any shader at any stage can access any material property or texture that they might need without having to add in new C++ code to make them available to that shader. This makes adding new shaders that work on different parts of the data very easy.

This technique is used by id Tech 7 and can be read about here: https://advances.realtimerendering.com/s2020/RenderingDoomEternal.pdf

A lot of this is also covered in the “3D Graphics Rendering Cookbook” and “OpenGL SuperBible 7th Edition”.

Entity and Light Changes

The first thing the renderer does is to do a check over entities and lights marked “dynamic” to see if any of them have changed within the last frame or if new ones have been added. The reason this is done is for two reasons:

1) If no entities have been changed or added, previous render queues may be entirely valid for this new frame and can be reused.

2) If a light has not moved or had an entity move near it, its shadow map data from the previous frame can be reused.

Anything marked as static is skipped during this step to save on performance.

Shader Recompile

Next up is a check to see if the application code has requested a shader recompile. If so all shaders are marked as invalid and the latest code is loaded from disk and compiled.

This capability was added very early in development since having it saved tons of time. A lot of shader effects were written and debugged while the engine was running.

GPU View Frustum Culling & Mesh LOD Selection

(Visual of the scene’s Axis-Aligned Bounding Boxes (AABBs))

The CPU then dispatches a compute shader which is responsible for culling draw commands by performing a visibility test of its Axis-Aligned Bounding Box (AABB) against the view frustum.

If a command passes the view frustum test meaning the mesh it represents is at least partially inside the frustum, the compute shader then checks to see how far away in view space that mesh is. Based on the distance it decides which LOD should be used, and finally writes the command to a GPU draw command buffer.

If a command fails the view frustum test meaning it’s fully outside at least one of the frustum planes, the GPU marks that command as unnecessary by setting its instance count parameter to 0.

This is a demonstration of how rendering queues backed by GPU draw command buffers enable the GPU to generate its own work. It’s able to take the global rendering queues and create a new rendering queue with only the draw commands that represent mesh geometry that is inside the view frustum.

Shadow Map Cache and Updates

Point lights and virtual point lights pull from their own shadow map caches. Regular point lights use a higher resolution shadow map pool (256x256 and 512x512 both seem to work well), while virtual point lights use a much larger but also much lower resolution shadow map pool.

For each light active nearby the camera, the renderer checks to see if its shadow map is already in the cache and the light hasn’t been marked as invalid. If so its shadow map data is reused. If not then its shadow map has to be regenerated.

To save on performance, no more than 3 shadow map updates are performed per frame. Each light is entered into a light update queue to prevent any light from being neglected for too many frames.

After the point lights, cascaded shadow maps are regenerated for the directional light (if enabled). Each of the four cascades are given the scene at different levels of details. The first cascade uses the highest level of detail while the last cascade uses the lowest available level of detail. This is done to save on performance while still giving accurate shadows at a close range.

(Shadow map cascades 1 (top left), 2 (top right), 3 (bottom left), 4 (bottom right))

GBuffer (Geometry Buffer) Generation

Now the GBuffer is generated so that it can be used with the deferred lighting and post processing passes. World space positions are reconstructed from the depth value so an explicit world space texture is not used. These are the following textures that are part of the GBuffer for this implementation:

1) 16-bit World space normal texture (converted from tangent space -> world space)

(It was pointed out to me that GBuffer normals can be handled more efficiently. See here: https://aras-p.info/texts/CompactNormalStorage.html)

2) 8-bit Albedo texture

3) 8-bit Base Reflectivity texture

4) 8-bit Roughness-Metallic-Ambient texture

5) 16-bit Structure buffer

(Structure buffer)

(Structure buffer)

The structure buffer is composed of three elements:

- Partial derivative of camera-space depth with respect to current x window coordinate

- Partial derivative of camera-space depth with respect to current y window coordinate

- Camera-space depth

The partial derivatives are calculated by the fragment shader using the dFdx and dFdy functions in GLSL: https://registry.khronos.org/OpenGL-Refpages/gl4/html/dFdx.xhtml

This buffer is very useful for various post-processing effects.

Physically Based Direct Lighting (Metallic-Roughness Pipeline)

The current PBR implementation for this engine is based on the PBR paper released by Google’s Filament team. This can be found here: https://google.github.io/filament/Filament.md.html.

Right now the standard model single scattering bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) is used by the engine so it will unfortunately lose energy at high roughness values. The diffuse term is using the Disney model since I liked the results a bit better even though it cost a tiny bit of performance. Google’s Filament heavily targets mobile so they found it to be not worth the extra computation, but since Stratus is only meant to run on desktop it should be ok in this situation.

Global Illumination

Global illumination is handled using virtual point lights (VPLs). This is conceptually very similar to the Instant Radiosity approach.

For this implementation virtual point lights are scattered around the scene either by hand or algorithmically or both. In order to save on performance the following assumptions are made:

- Single bounce indirect diffuse is generally good enough for the test scenes I’m using.

- Only static geometry will participate fully. Dynamic geometry can receive indirect light but won’t occlude or cast light. This allows me to heavily reuse diffuse and shadow maps.

- All VPLs can potentially cast shadows. Their shadow data is heavily reused between frames.

- VPLs themselves are kept around between frames even if they’re not currently active so they can be reused later.

The application is free to spawn and despawn VPLs at runtime.

Here is an outline of the algorithm steps:

1) Collect all candidate VPLs nearby the camera. These are then sent to a compute shader which checks them against the cascaded shadow maps to see if the VPL is visible. Each visible VPL gets its color by sampling its local diffuse map along the direction the world light is oriented. This color is combined with the world light color + intensity to arrive at a final color per visible VPL.

2) Another compute shader splits the screen into tiles which are each 2x4 pixels in size. For each tile, the average position and average normal is computed by sampling the GBuffer.

3) The list of visible VPLs and averaged position/normal per tile is then taken by another compute shader which narrows down the 6 most important VPLs per tile.

4) A fragment shader determines which tile group its pixel belongs in and calculates lighting for each of the 6 VPLs that belong to that tile. The output for this stage is a screen diffuse light map with only the indirect illumination.

5) Another fragment shader performs blurring of the diffuse indirect light map and additively combines it with main screen texture.

(Output from step 4 from above - only indirect illumination is present)

(Output from step 4 from above - only indirect illumination is present)

(Output from step 5 from above - indirect illumination is blurred and combined with main screen texture)

(Output from step 5 from above - indirect illumination is blurred and combined with main screen texture)

Screen Space Ambient Occlusion

This implementation is based on the SSAO chapter found in “Foundations of Game Engine Development, Volume 2: Rendering”.

This algorithm runs in two passes. The first pass builds a buffer which represents how much ambient light reaches a given surface. If the value is low the result is less ambient light for that pixel. To build this buffer, a fragment shader samples the structure buffer in 4 places around the current pixel. What it is trying to do is use the structure buffer’s information to figure out if there is nearby geometry that is occluding ambient light that would otherwise be reaching the current surface. The 4 places that the fragment shader reads from are randomly offset by a 4x4 rotation texture that we precompute on the CPU. This rotation texture is set up and used in such a way that for every 4x4 group of nearby pixels, their structure buffer sampling patterns will amount to 64 unique samples.

(Output from the first SSAO pass)

(Output from the first SSAO pass)

Looking closely there is a dotted pattern present in many parts of the texture. If this result were used directly it would result in low quality SSAO. To get around this a second depth-aware blurring pass is used. To do this the camera-space depth from the structure buffer is used.

Now all the dotted patterns have been smoothed out. This blurred SSAO buffer is combined per-pixel with any ambient term to reduce the ambient intensity for any surface where it has been estimated to be occluded.

Volumetric Lighting and Shadowing

This implementation is based on the atmospheric shadowing chapter found in “Foundations of Game Engine Development, Volume 2: Rendering”.

The purpose of this step is to simulate how light interacts with participating media, which could be things like water vapor or dust particles. These are the high level details of the model used here:

1) Some fraction of light traveling through the air will be redirected towards the camera (inscattering)

2) Some fraction of the light traveling through the air will be redirected away from the camera (outscattering and backscattering)

3) Some will be absorbed by the participating media and not reach the camera (extinction)

4) Some is occluded completely due to a distant object blocking rays of light.

The result of this is that parts of the scene will appear foggy or hazy while still allowing the viewer to see through to the other side. When there are distant objects blocking light rays, there will be noticeably darker areas in the fog which give the appearance of light rays/God rays (also known as crepuscular rays). This is very noticeable when in a forested scene or when light is streaming through a window but is partially blocked by the central frame.

This Digital Foundry video explains it very well: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0sYTrX3VHI.

To accomplish these effects the renderer performs raycasting in camera space and uses the cascaded shadow maps combined with the structure buffer. For each pixel, one ray is cast and sampled along 64 non-linear locations (exact sampling count configurable at runtime). The sampling density is highest at points along the ray closest to the camera and sparsest at points that are furthest away from the camera. We end the sampling early if the ray runs into some geometry which is checked by using the structure buffer.

For each sampling step, if that location is not in shadow after checking it against the cascaded shadow maps, it applies a fog model which estimates how much light is inscattered towards the camera based on the current distance along the ray. If it is in shadow that sample is skipped. These steps are accumulated into a final value per pixel which can be blended with the main screen texture.

(This is the result from the volumetric lighting pass using the San Miguel scene with StratusGFX)

(This is the result after combining it with the main screen texture)

Post Processing

During the post processing step the following take place:

- Volumetric information is combined with direct/indirect lighting

- A bloom filter is applied which is based on the Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare presentation: http://www.iryoku.com/next-generation-post-processing-in-call-of-duty-advanced-warfare

- Tone mapping is applied to map HDR values to LDR values using ACES Filmic Tonepping described here: https://knarkowicz.wordpress.com/2016/01/06/aces-filmic-tone-mapping-curve/

Fast Approximate Anti-Aliasing (FXAA)

After tonemapping and gamma correction, FXAA is applied. This is done using a non-linear series of steps to identify edges and apply blurring. A final guess step is taken if the end of the edge was not found within 10 steps. For more information see https://catlikecoding.com/unity/tutorials/custom-srp/fxaa/.

Temporal Anti-Aliasing (TAA) -> New in engine version 0.10 (experimental, in development)

TAA is used to supplement FXAA since it can help stabilize the scene while in motion. It is applied at the beginning of the post processing pass so that it can help reduce flickering with things like bloom.

To accomplish this a very slight subpixel jitter is added using numbers from the base 2, base 3 Halton sequence. Per pixel and per object velocity is taken into account when the camera or an object moves. Basic color clamping helps reduce ghosting artifacts.

For more information see the following articles:

- https://sugulee.wordpress.com/2021/06/21/temporal-anti-aliasingtaa-tutorial/

- https://ziyadbarakat.wordpress.com/2020/07/28/temporal-anti-aliasing-step-by-step/

- https://www.elopezr.com/temporal-aa-and-the-quest-for-the-holy-trail/

- http://extremelearning.com.au/unreasonable-effectiveness-of-quasirandom-sequences/

- https://de45xmedrsdbp.cloudfront.net/Resources/files/TemporalAA_small-59732822.pdf

Future of StratusGFX

I will likely continue working on this rendering engine to some extent so that I can keep researching and learning about graphics programming. These are the areas I am strongly interested in going forward:

- Porting the renderer to Vulkan

- Switching to a global illumination approach based on either voxel cone tracing or ray traced signed distance fields (or maybe another approach? I am not sure yet)

- High-quality anti aliasing even while the camera is moving using Temporal Super Sampling Anti-Aliasing (TSSAA) which was showcased in Doom 2016

Helpful Resources and References

- https://learnopengl.com

- 3D Graphics Rendering Cookbook

- OpenGL SuperBible

- Foudations of Game Engine Development, Volume 1: Mathematics

- Foundations of Game Engine Development, Volume 2: Rendering

- Physically Based Rendering Online Book

- Game Engine Architecture

- Biskwit’s YouTube Channel

- Cem Yuksel’s YouTube Channel

- Fabien Sanglard’s Website